Me, Myself, and a Good Meal

Eating solo means eating however you like and that includes licking the plate. Dining alone isn’t always a delight, but it can be.

I’ve been circling around this week’s theme for a few days and the idea that kept tugging at me was the simple act of challenging ourselves when we eat. Not in a competitive, chilli-eating-contest kind of way, but in a more personal sense: noticing the edges of our comfort zone and occasionally nudging them outwards.

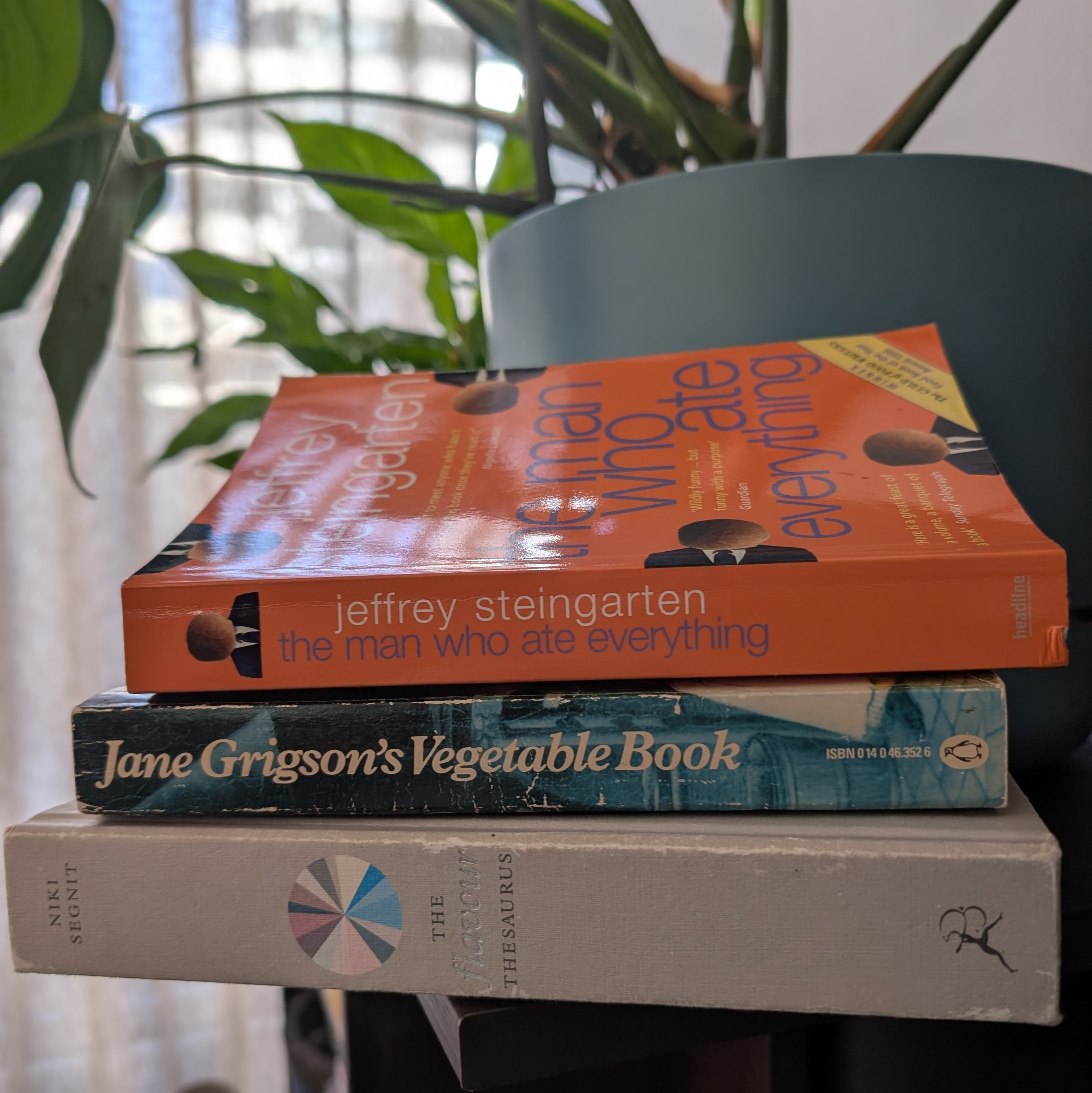

Jeffrey Steingarten writes about this beautifully in The Man Who Ate Everything. When he was appointed the food critic for Vogue in 1989, he realised his “ intense food preferences, whether phobias or craving, struck me as the most serious of all personal limitations.” He had a long list of food phobias: insects, kimchi, dill, swordfish, anchovies, lard, and even desserts in Indian restaurants. Instead of tiptoeing around them, he created a six-step program to liberate his palate. Through plain and simple exposure, many of the foods he once couldn’t bear became dishes he genuinely enjoyed.

While I have not been summoned to the hallowed halls of Vogue, I understand the impulse. Our ideas of what is ‘normal’ to eat begin at home. They stretch and shift as we venture further into the world, gathering influences from friends, cultures, travel, and the happenstance of what we’re offered. The foods I grew up eating seem completely natural to me; other flavours took longer routes before settling into my rotation.

It’s a vegetable that seems to divide people neatly into camps. Some love its soft, silky interior and capacity to absorb flavour. Others recoil, convinced it’s destined to be bitter or soggy. I was somewhere in the middle for years, dutifully eating it but ‘never craving it. That changed slowly—dish by dish, recipe by recipe—as I learned how much versatility hides beneath its glossy skin.

Jane Grigson, in her writing on aubergine/eggplant, leans heavily into the Mediterranean. Her recipes swing through caponata, moussaka, parmigiana di melanzane (always satisfying to say regardless of your accent), and ratatouille. No mention of baba ganoush, though. A pity, because charring an eggplant over a flame is something everyone should do at least once. The smell alone is enough to make you feel you’re doing something primal, and that char is what gives baba ganoush its essential smoky character.

More recently, I’ve been turning to Nikki Segnit’s The Flavour Thesaurus when I want to understand ingredients from a new angle. Her entry on aubergine is a delight. “Short of taking a surreptitious nibble, the best way to check if an aubergine has the requisite flavour and texture is to test its tautness. Ideally an aubergine should be as tight and shiny as dolphin skin. Similarly, they squeak when you pinch them.” For the record, I have never pinched a dolphin but I now find myself giving eggplants an investigative prod whenever I pass one.

Segnit’s list of pairings is a helpful roadmap: capsicum, chilli, garlic, ginger, lamb, nutmeg, prosciutto, soft cheese, tomato, walnut. Ingredients that nudge eggplant toward sweetness, smokiness, or warmth. Ingredients that help it stand tall rather than become drowned in oil or collapse into nothingness.

All of this brings me to a meal my partner and I had recently at Ho Jiak, a Malaysian restaurant in Melbourne. It was a spontaneous choice and one dish in particular made the evening— Eggplant Bersira with acar caramel and umami cream. I’ve eaten braised eggplant in plenty of Asian styles, but nothing quite like this.

Fat fingers of eggplant were lightly battered, deep-fried until tender inside and crisp outside, then coated in a glossy acar caramel that managed to be sweet and savoury all at once. They were arranged on a bed of deeply savoury cream that brought everything into balance.

I loved it immediately. My partner, who has long been hesitant about eggplant, took one bite and paused before digging back in swiftly. He went from reluctant participant to enthusiastic convert before the plate was empty. And that is the part that stays with me. Sometimes all it takes is the right version of a dish—or the right context—for something previously unappealing to click.

Steingarten pushed himself to overcome his culinary fears through discipline and curiosity. Most of us don’t need a structured programme, but we can steal his approach. We can notice the ingredients we avoid and ask ourselves why. We can try a familiar ingredient cooked in an unfamiliar way. We can order the thing we’d normally skip. We can allow ourselves to be surprised. And every now and then, if we’re lucky, a plate of eggplant can open a small new door.

Eating solo means eating however you like and that includes licking the plate. Dining alone isn’t always a delight, but it can be.

Earthy roasted purple and golden beetroots are natural bedfellows to a mellow goats cheese. Leaves of roasted red onion add a sweet dimention - plus it's pretty as a picture.

A St John-inspired birthday feast in high summer - what was I thinking?